-

JACOPO MANDIĆ’S “MIRROR OF THE WORLD”

-

Address:

-

Partners:

This is Italian sculptor Jacopo Mandić.

And this is Satka, an Ural town.

How a citizen of the Eternal City, a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts happened to be in the Urals? He is a part of the new history of the old industrial center, like hundreds of famous artists of our planet. Artists from Italy, Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, South Africa change the face of the manufacturing town with two-hundred-year working experience.

Invisible Power

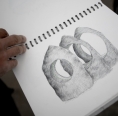

“I wish you knew the kind of garbage heap wild verses grow on”… Tones of Jacopo Mandić’s “verses” grow on stone and pieces of wire, wood and iron… You can feel the energy of his sculptures not even being an expert in contemporary art. The artist’s manifestos captured in stone and metal are like chopped, bristling Mayakovsky’s rhymes. Filigree work with sound there, and “weighty, rude, visible” material and ephemeral implications here. “The rhyme brings you back to the previous line, reminding you all the words” that make a completed utterance…

—What are you talking about with the world? What are you trying to tell people with your sculptures?

Jacopo Mandić, a sculptor, a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts, and an Art Residences program participant:

—Most of the time, it’s about things you cannot see with your eyes… About latent energy.

This stone, for example, contains the history of the Earth. It is the “skin” of our planet! Do you see these lines? Just think of it! This pattern may have been created millions of years ago… Each vein is a part the Earth’s history. Frozen time!

Every stone or piece of iron for me is not just working material. They are mirror of the world! The mirror that reflects millennia of the history of our planet. They are containers of the entire world! And, for me, it is very important to open this invisible world to other people. To draw attention to something many of them do not notice in their everyday lives. To show invisible power of stone, wood, metal…

“A Very Personal Talk with the World”

“An artist begins when his own system of thoughts about the real world emerges in his head. That’s when the things he creates is called art,” Andrei Tarkovsky believed. A great artist called his works “canned time” while Jacopo’s task is quite opposite: to open these “canned time,” to liberate invisible power of the natural material that saw so much.

—Is it important for you as an artist to be always understood by everyone?”

—It’s unnecessary. Not at all. Many masters do not care whether they are understood or not. It does not affect the artist’s path. He just does whatever he sees fit. Contemporary art has many styles and many languages… Ways to talk with the world… Who understood great Malevich in Russia a hundred years ago? His “Black Square”? But this work was revolutionary! It opened a door to a new reality!

The attitude to my sculptures always differs. Their perception may be affected even by time and place. Some people think being a contemporary artist in Rome is much easier than somewhere in the Urals. Not at all! The attitude to art objects there is pretty much the same.

—What idea you would call the “dream project”?

—It’s the first version of the sculpture from the “Invisible Power” series that I wanted to make in Satka this summer. This art object was my biggest dream.

But we took a simpler approach. We decided that people here will not understand my work. I influence minds and souls of people with soft power. I’m not for all that epatage, shocks.

The sculpture I wanted to create was to be my confession… A fusion of many implications… And, first of all, it had to express the things I didn’t express yet as an artist.

“Hot” Rock

—You decided to choose magnesite for your new works. Why is that?

—I’m working now on a big project called “Invisible Power” which should combine three art objects. We were considering the possibility to work with various materials. I chose magnesite because it offers a wide range of options and well fits for creation of big sculptures. It’s also a symbol of Satka. I associate this rock type with nature and people here.

—Speaking of the nature of this rock from a human point of view… What kind of “guy” is this rock magnesite? How hard is to deal with it?

—Its nature is strong and “hot.” But, at the same time, its very vulnerable. Magnesite is a fire resistant material. It does not burn even in fire, but it’s very fragile and can be easily cracked. It’s not the rock you can use to create, say, a classical Greek sculpture. But it kind of unique since very few natural materials can withstand high temperatures. I’m looking for new applications of magnesite. I wonder how it will behave together with other materials. My goal is to show its invisible power!

12 Tons of Hope

The saying is “All roads lead to Rome,” but Satka can easily challenge it today. A few years ago, the Ural manufacturing town was both Rome and Mecca for artists from around the world.

Jacopo encountered Satka in 2015 in the 3rd Ural Industrial Biennale of Contemporary Art. The art object “Explosion” installed on one of the main streets of the regional center is a reminder of the Italian’s last visit of the town of metallurgists.

Four years later, Mandić returned to Satka to bring to life his “dream project” called “Invisible Power.” Here, in the Urals, he first tried to work with a large sculpture. “I could never implement this project in Italy. I just couldn’t get a 12-ton stone there! And my boss solves all my problems here!” the sculptor says.

Jacopo’s boss in Satka is Anna Dubrovskaya, a Sobranie Fund representative. The Fund is also a “think tank” for social and cultural transformations in the region. It’s a solid entity, in every way. Its business partners are Magnezit Group, the Satka District administration, embassies of several European countries, the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), the Tretyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum, and dozens of other entities with big names.

Anna Dubrovskaya, a Sobranie Fund representative:

—It’s the first time when Jacopo creates such big sculptures. For him, it’s also an experiment. Finding material fit for a such big art object in Italy it’s not an easy task. But here, we can do it. When we contacted the sculptor and offered him to visit Satka again, he was very happy. We tried to make the master’s work comfortable. It’s an approach we apply to every artist.

—How many foreign artists invited by Sobranie Fund have already visited Satka?

—About a hundred… From Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland…

—Why do famous masters come here? What brings them to the town “deep in the Urals”?

—When Sobranie Fund decided to hold the first international Satka Street Art Fest in Satka, we just invited the people who were of interest to us.

Artists from around the world painted facades of model high-rise buildings in Satka. It’s when the Art Residence appeared in the town. I think, Satka interests them as a place to gain a new experience. Another point is very good attitude to artists here.

—And what is Satka residents’ attitude to the contemporary art objects?

—It varies. Many people here don’t like them. I remember one man’s response. He said paintings on the walls is a terrible thing because they do not fit in the general pastel colors of the town’s architecture.

—Is it hard to break the “beauty” stereotypes?

—Yes. It’s hard for all pioneers. But we already see changes. The energy of creation turned out to be contagious. We see how the town is changing, how the people are changing. Once critics, they suddenly become our allies. I think street art makes the town brighter, ennobles it.

“I am Italian! And I’m alive! Great!”

Locals still remember the happy Roman among rock placers of one of Satka’s industrial quarries.

He explored the dumps meter by meter like a little boy who discovered a cave of gems. For every stone was a potential sculpture!

They say local workers used to peek from time to time into the studio where sounds of working angle grinder, drill or welder were heard all day, to take a look at the Italian master and have a talk about life. “He’s our man!” many of them thought.

—When I hear the phrase “Italian sculptor”, it always reminds me of such synonymic chain as “a representative of ancient culture”, “an apologist of classical art school.” How often do you face such attitude to you?

—I faced a situation in 2015: one of the factory workers saw me and exclaimed: “Oh! The first alive Italian!” First, I was shocked: “What?!”. And then he rejoiced: “Oh! Wow! I am the only Italian! And I’m alive! Great!”.

Am I a “representative” of ancient culture? A very common belief about Italian artists in the modern world is: “They are stuck in past centuries.” Maybe, it’s true. Maybe not. I don’t know. I think, there are many Italian artists whose work affects world culture trends today.

—Do they understand contemporary art language here, far from the European centers of culture?

—Like anywhere else, some people here like it, and they are ready to perceive artist’s messages, while others do not want to delve into the philosophy of works. I saw many people in Satka who are very glad that artists from around the world are working to change the town’s industrial landscapes. There are also those who would prefer Satka to retain the traditional style of local architecture. It is normal. It happens everywhere in the world.

—Even in Italy?

—Yes. Some people believe their cities’ faces should be formed by local artists. Just because they are “our people.” “Our!” That’s the key word! They won’t go beyond common tastes. But I think it’s very important to establish connections between local people and representatives of another culture who work in an unusual style, who have a different view on many things, who break some stereotypes. And I feel it with my skin how hard it is to establish such connection… How hard it is to perceive another culture… I understand that the way I chose as an artist is not the easiest one. But for the territory where I’m working now, it’s also a non-standard way of development.

Between Satka and Rome

—What stereotypes did you lose in this journey from Rome to Satka?

—First, I realized that wandering is good for artist. Second, I gave up the stereotype of Russians as of cold, harsh people. Now I know that it’s not so. They are open for warm, human contacts.

Satka is a small town. Living here is hard. But I saw a lot of people who treated me much like my mom did. Italians are believed to like gesturing. And I observed it in people here, too!

—What do you think about the local authorities’ idea to combine the industrial style of the old Ural town with objects of contemporary art? How much do you think is this symbiosis viable?

—Industrial spaces and objects of contemporary art do coexist pretty well in many countries. It’s a common practice. Industrial sites become cultural centers, homes to exhibitions, museums, etc.

—What would you, as an Italian artist, change in an industrial town if you decided to personally rebrand the territory?

—In addition to gala Satka, I see another town. And a lot of things there have to be changed. There are lots of gray: gray stones, gray asphalt, gray sky. Lots of gloomy landscapes.

One idea is to make walkways bright, maybe, backlit. And there should be more greenery. For example, I really like those little flower beds Satka residents make near their houses.

—Do you think the new look of the town can affect quality of life of its people? Can the new form change the “old” substance?

—Yes, art can affect lives of specific people. But I don’t think it can rebuild everyone’s inner world. And I don’t think that, for example, my sculpture can radically change life of Satka dwellers. But it may help them to push limits of their vision of the world and contemporary art.

Each person should have a big dream. A dream of how they can change the world. I see a new generation of Satka residents that grows and is ready to transform the space around them.

—What will you tell your friends about the Southern Urals when you will return home?

—I will tell that it was a good experience for me. Both personal and professional. I discovered a lot of things I have never encountered before. I will tell that living here, next to the large factory, is not easy: hard work, harsh living conditions, severe climate. And it was summer when I worked in Satka! It would be much harder in winter.

And maybe, I will tell my Italian friends: “If you are invited to Satka, try it. It won’t be easy. But try it! It’s worth it!”.

Author: Natalya Isakova. Gornozavodskiye.

Photo: Nikita Isakov, Sobranie Found.

-

26.08 - 26.08

DIARY OF THE THIRD INDUSTRIAL BIENNALE

-

28.11 - 28.11

MY SATKA FESTIVAL WINS THE CONTEST OF CORPORATE VOLUNTEER PROJECTS

-

13.10 - 15.10

COOPERATION WITH VGIBL NAMED AFTER M.I. RUDOMINO